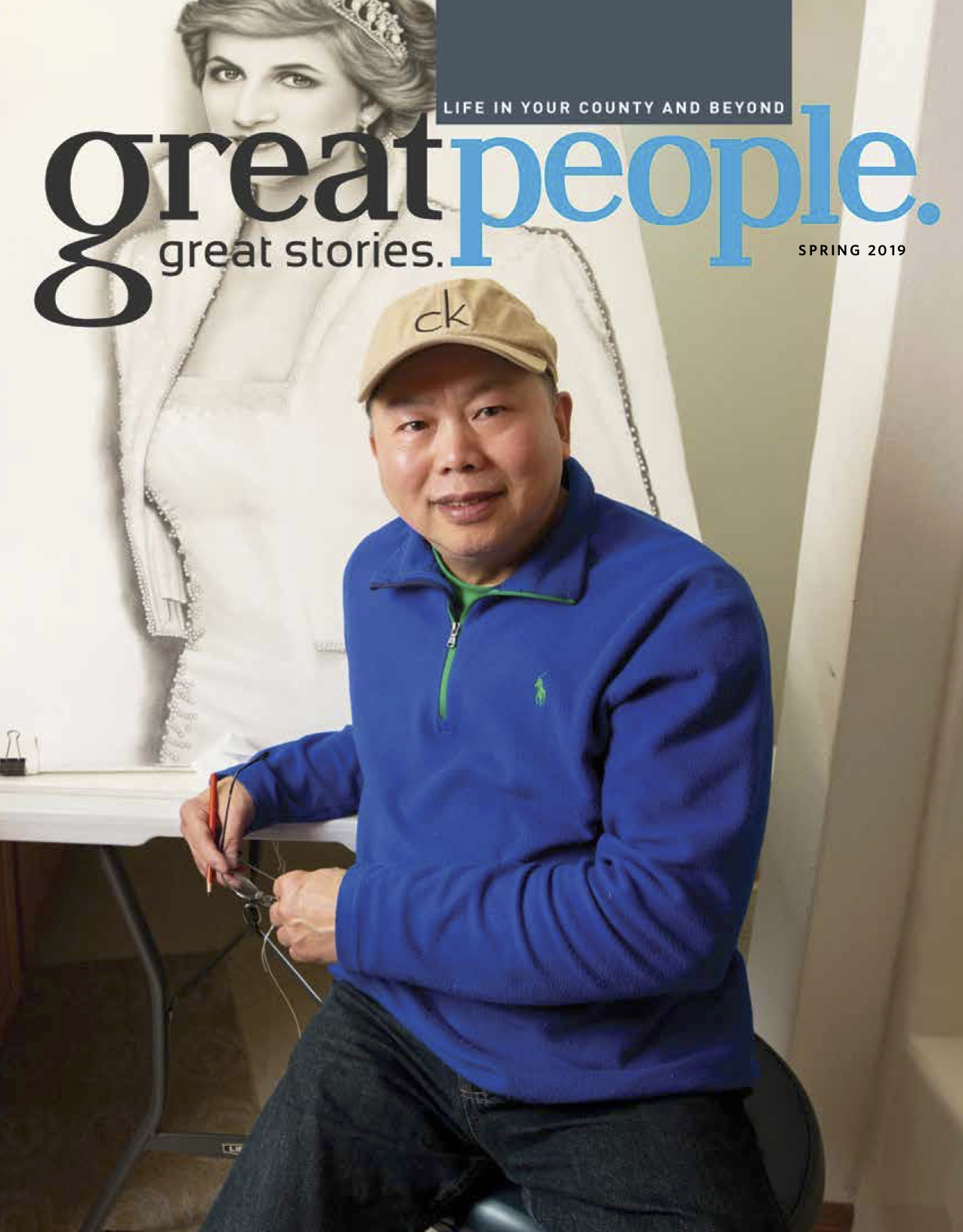

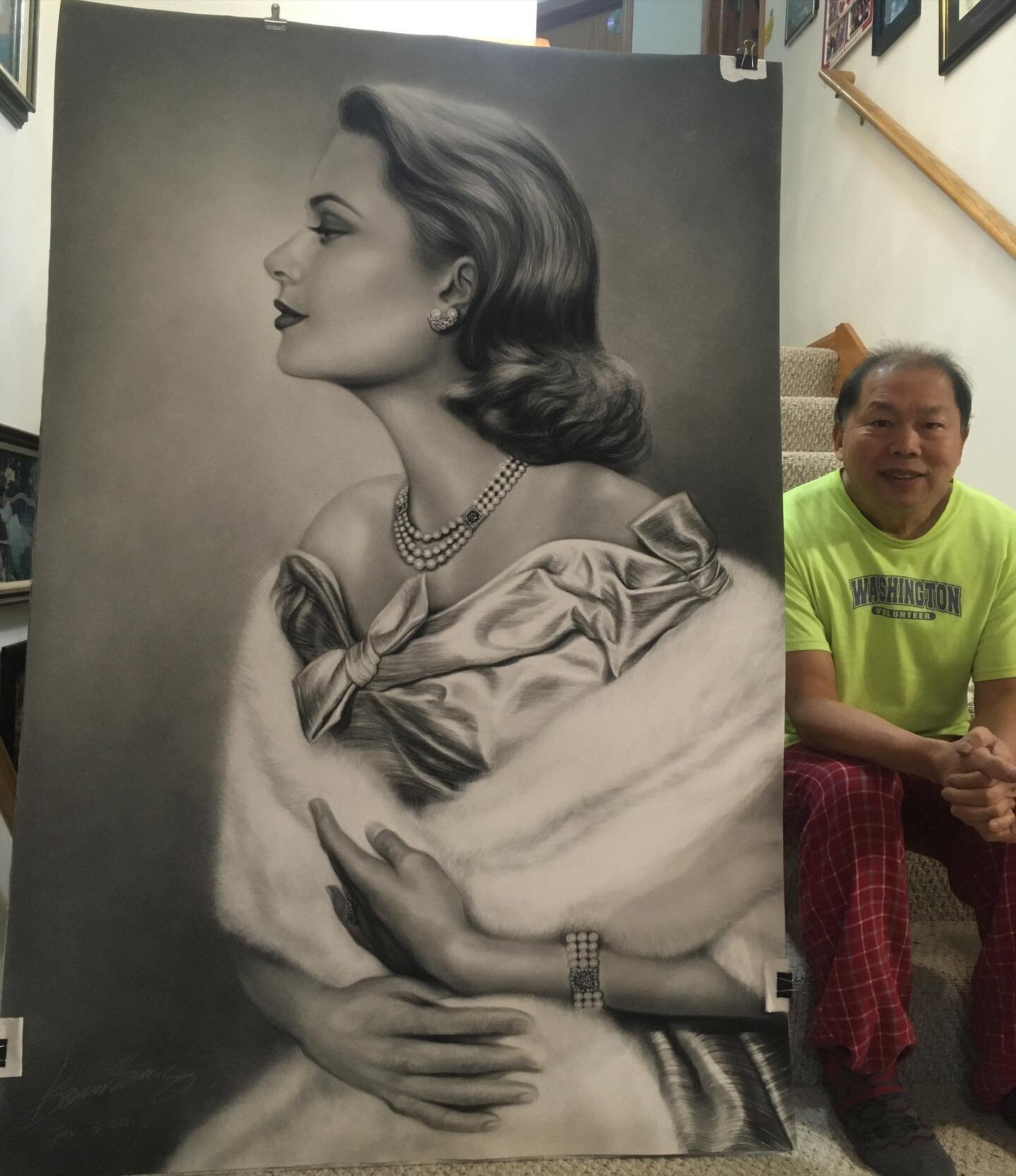

Dear Reader: I first heard of Bounsay Pipathsouk when a member of our editorial team came across his website — a site, I later learned, that was created by his youngest daughter. The site introduced him as a Laotian immigrant who has always had a remarkable talent for drawing life-like portraits of celebrities. Since this magazine is called “Great People. Great Stories,” I thought his story would be perfect for us, and I set out to arrange an interview with Bounsay and his wife, Pealuan. I met the two of them at their business, Bounsay’s Upholstery Service in Rockford, where they had set up about a dozen of Bounsay’s favorite drawings of female celebrities. I settled myself in for a good story … and I couldn’t believe my ears. This soft-spoken man’s story had everything: intrigue, a daring escape from an oppressive country, the classic tale of an immigrant who wants to do everything he can to support his family, children who have risen to the top of the academic world, and, of course, an artist’s quest to chase his dream. It was like the plot of a movie — but it was a true story. You can find this true story on page 12. Bounsay and Pealuan are a good example of why I love my job: There is nothing more satisfying than meeting someone who has a wonderful story to tell, and sharing his tale with the rest of the community. It’s also why I love this magazine. Over the past few years, we have shared dozens of stories with the people who live in Winnebago County and its surrounding communities. And we always need more! I enjoy meeting people like Bounsay, who are just quietly going about their business, but who have an extraordinary story to tell. If you know someone like this, please contact me at editor@gpgsmagazine.com. It will make my day! Beth Earnest. Editor, “Great People. Great Stories.”

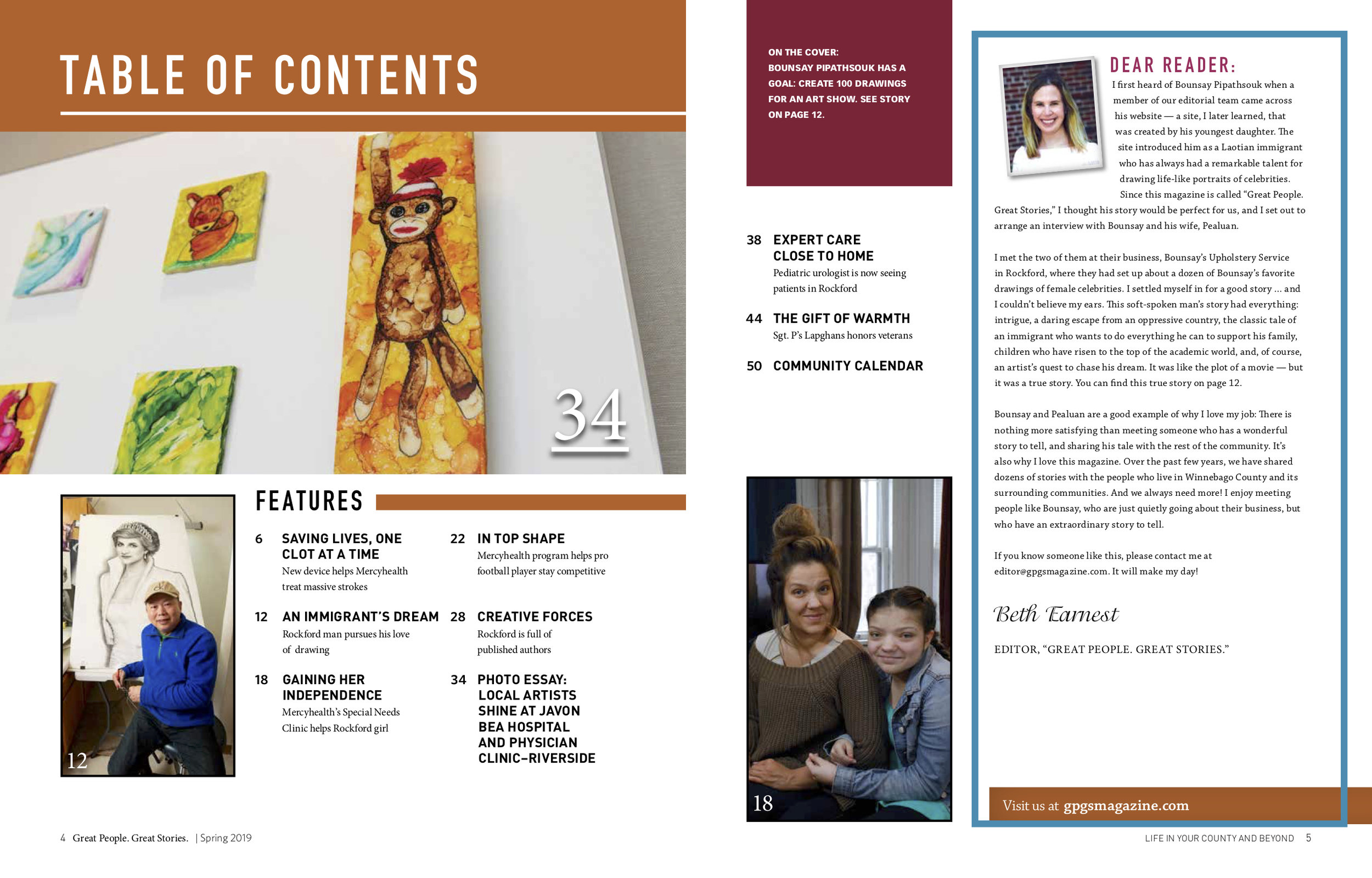

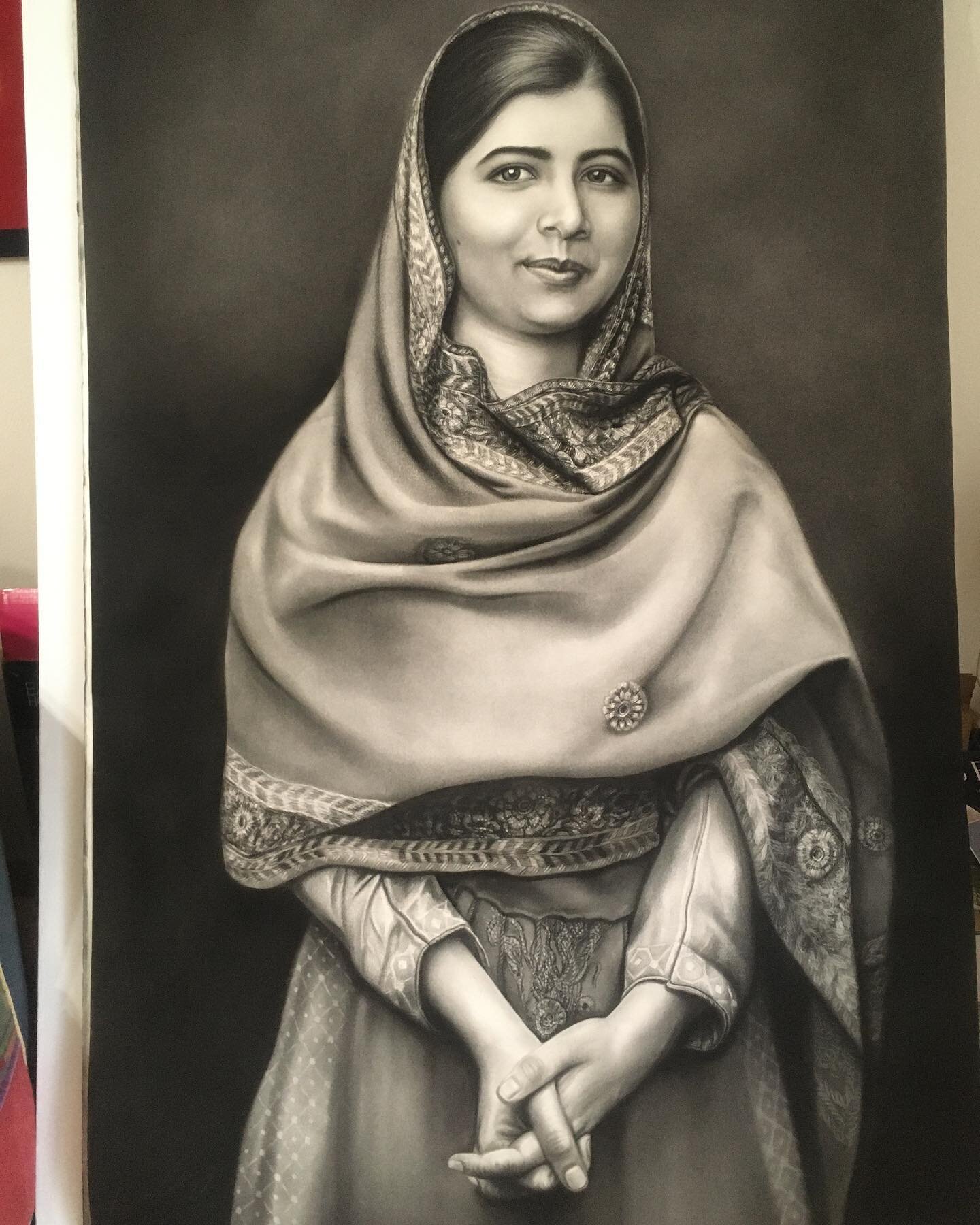

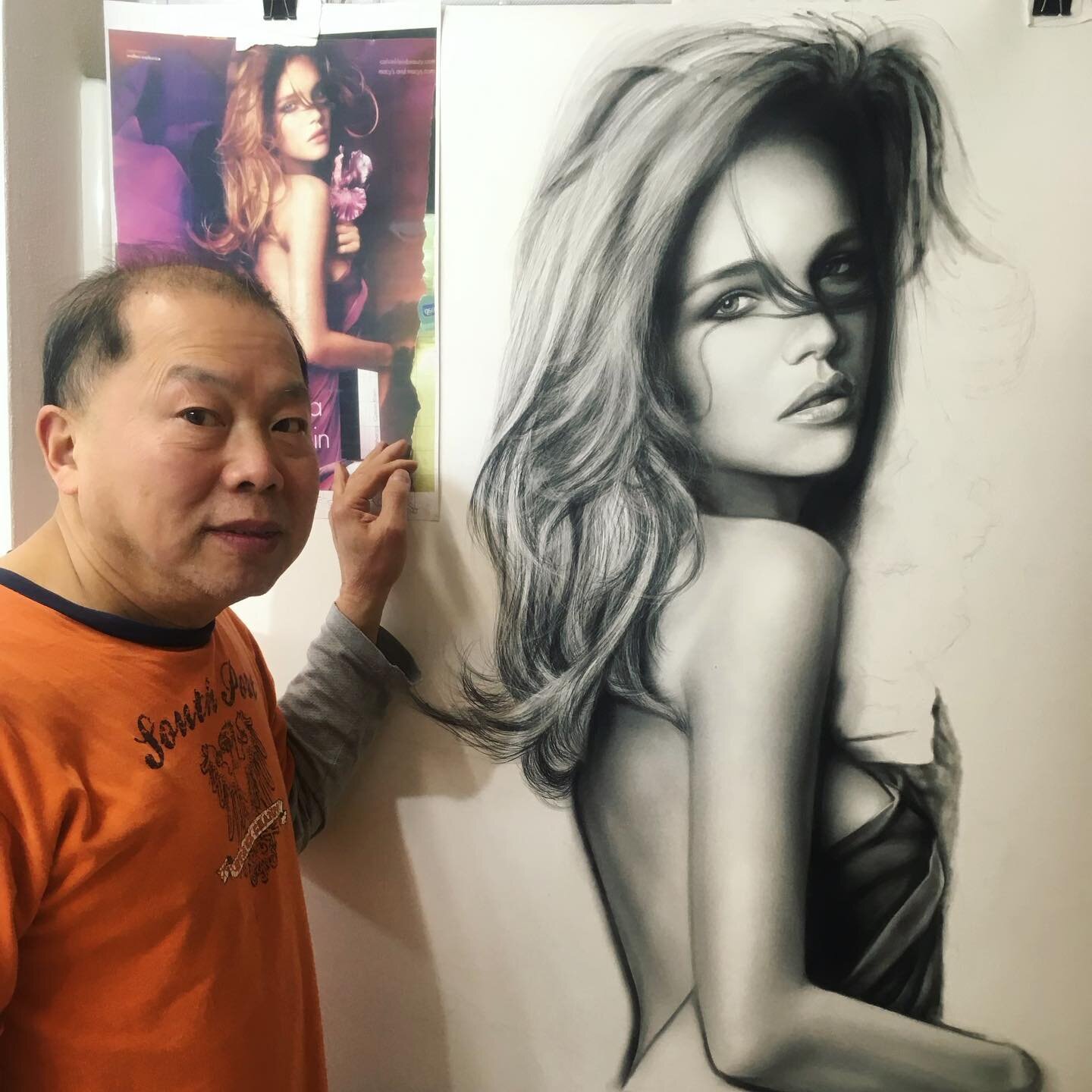

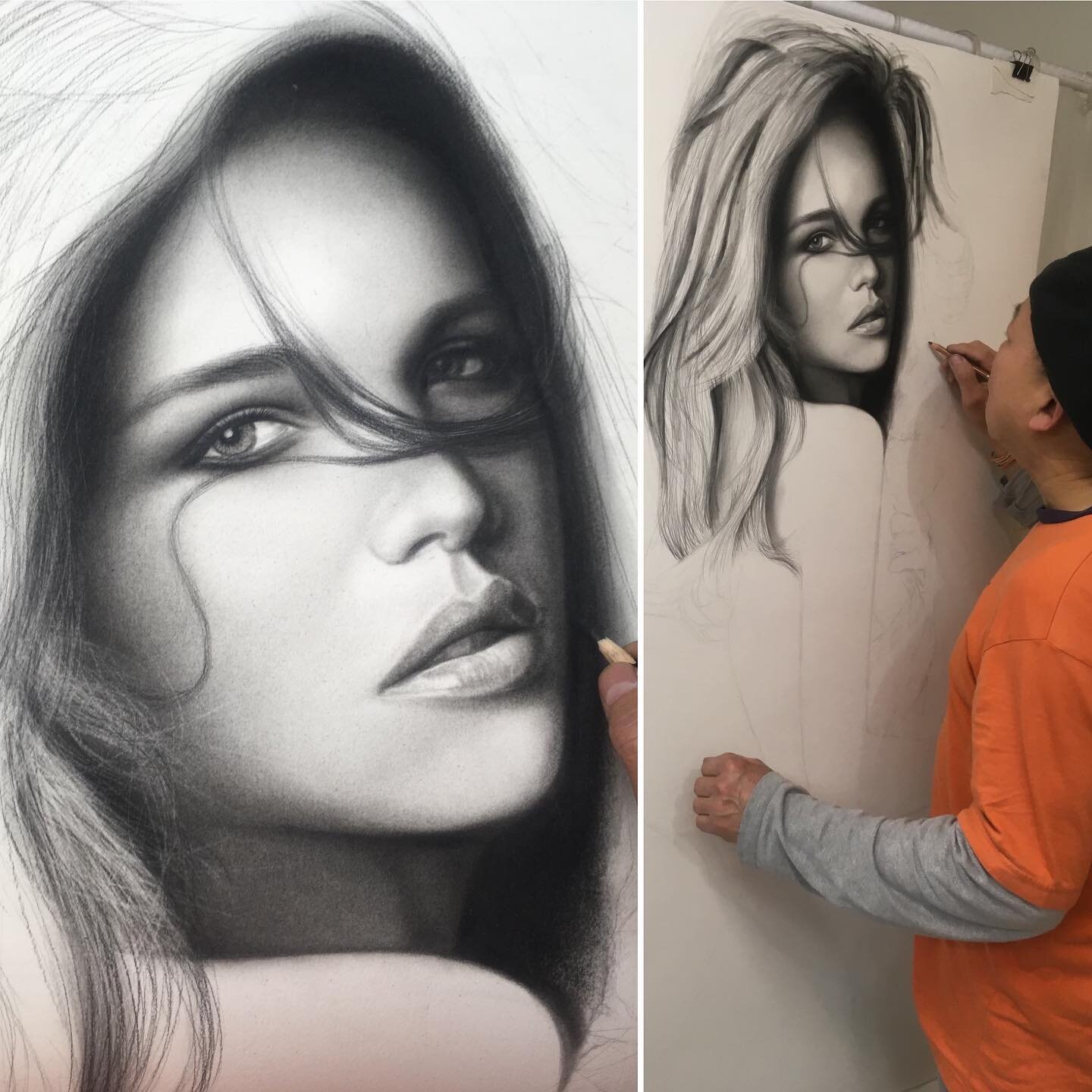

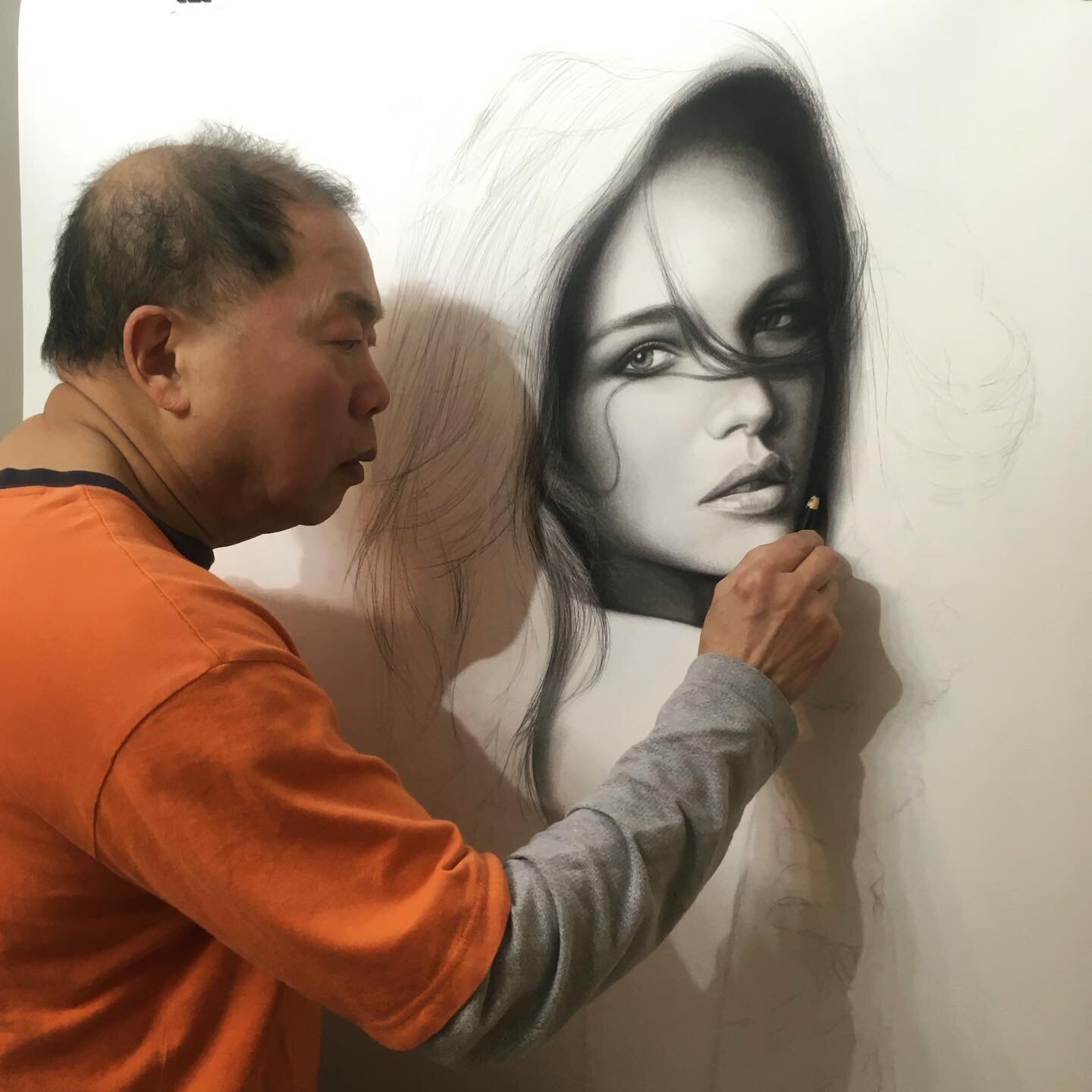

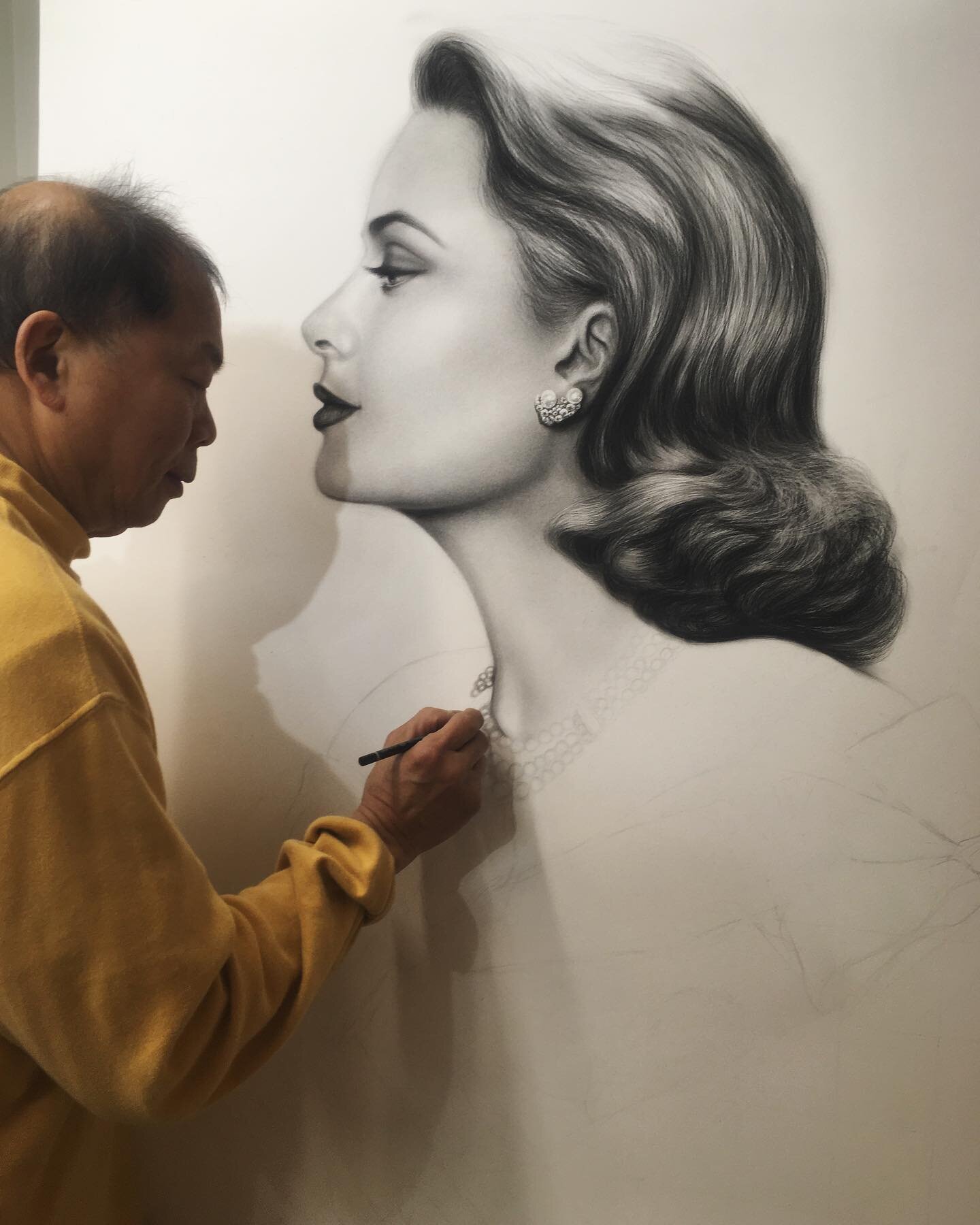

An Immigrant’s Dream - Rockford man pursues his love of drawing - When Bounsay Pipathsouk first fell in love with his wife, Pealuan, her family wanted to make sure he would be able to provide for her. They quizzed him about his intentions and ambitions, and he told them he was an artist, but he also had a “real” job as an upholsterer. Pealuan’s family advised him to forget about his drawing and concentrate on the kind of work that would allow him to provide for his family. Eager to please his soon-to-be in-laws, Bounsay agreed to put his drawing aside and focus his efforts on providing for his family.

He did just that: He became successful enough that he opened his own business just a year after they were married, and while he was never rich, he earned enough to put food on the table and help their three children earn full scholarships to college — two to Stanford university in California and one to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. But he never quite forgot about his greatest passion: drawing. And now that life is more financially comfortable for both him and Pealuan, Bounsay is pursuing the dream he has had since he was a boy.

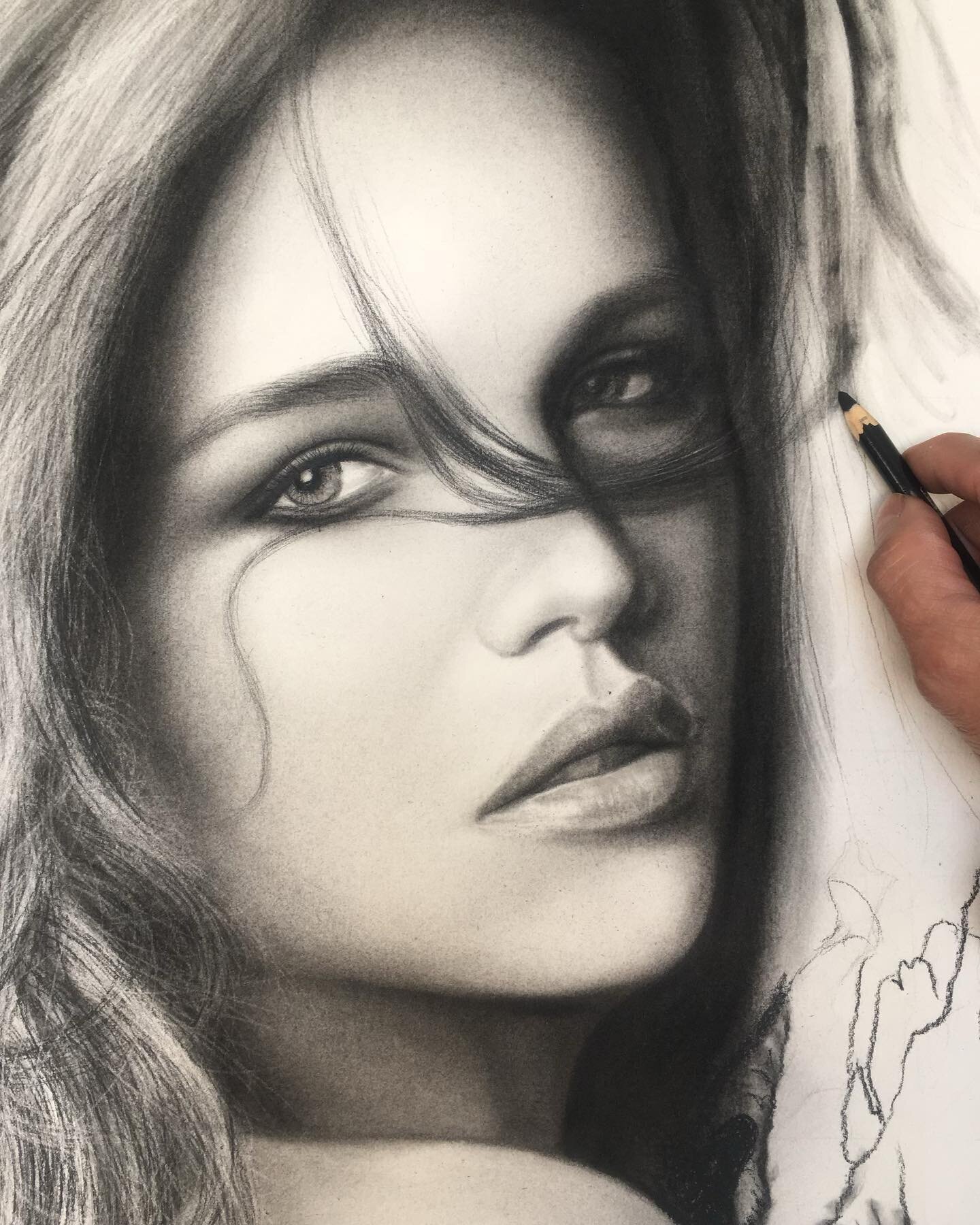

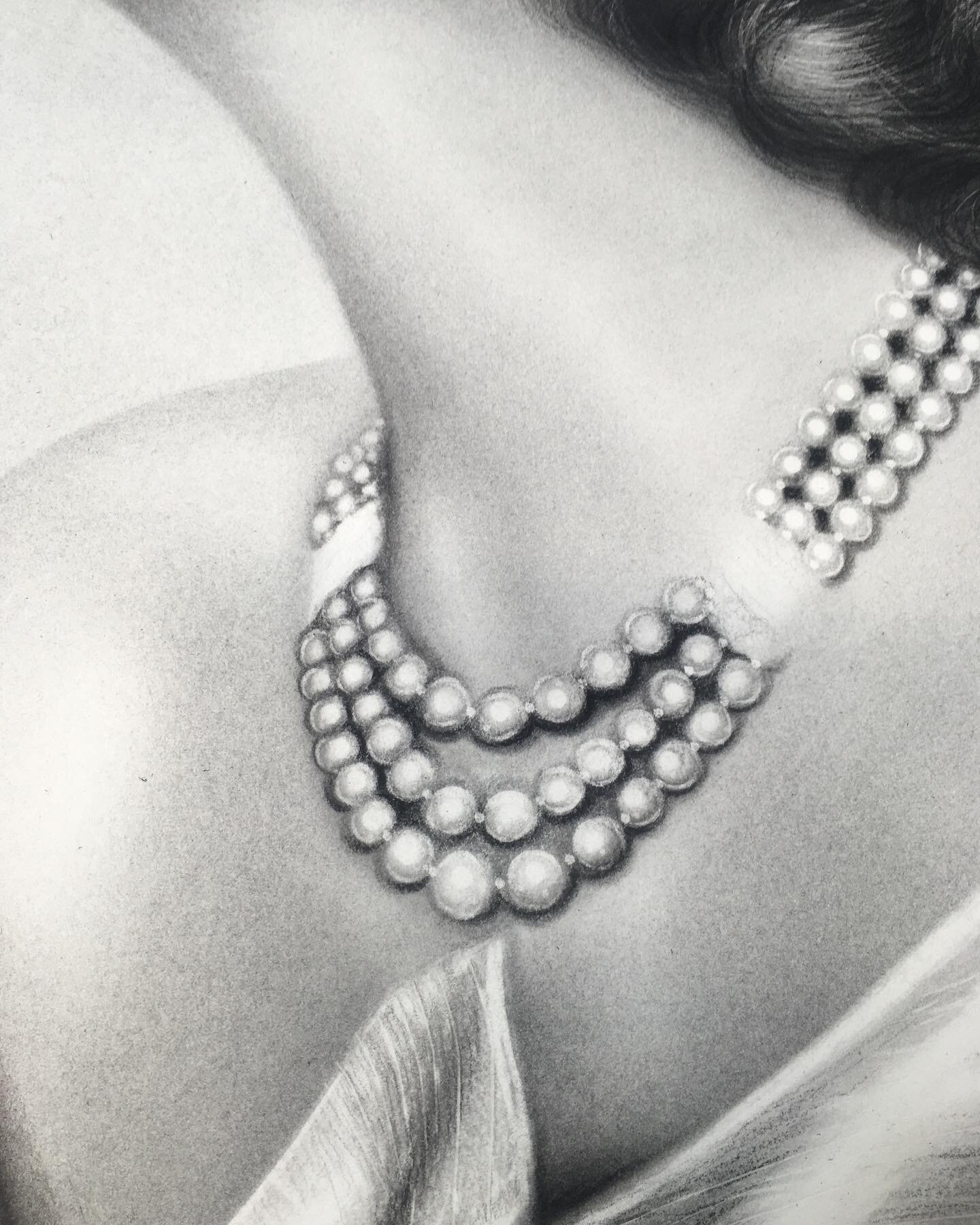

Struggling to Survive - Bounsay was born in Laos and lived with his father and sister (his mother died when he was young). They chafed under Communist rule, struggling to find enough food. “It seemed like we couldn’t survive anymore,” says Bounsay. “After our dog died of starvation, we thought, ‘Are we next?’” As more and more people moved out of their neighborhood to seek better lives in other countries, Bounsay and his family decided to make their own exit. They waited until the night of a thunderstorm, then took a boat across the Makong River to Thailand, praying soldiers wouldn’t see them and start shooting. They made it to a refugee camp in Thailand, where they stayed for two years while waiting for another country to approve their immigration. While they were there, Bounsay learned he could make a living drawing other people’s faces. Embassy officials and visitors to the camp saw his drawings of celebrities and paid him $20 for a charcoal or pencil drawing, which was enough to feed his family for a month, along with their United Nations ration. Eventually, the Pipathsouk family was cleared to enter the United States. They came here in 1978 under the sponsorship of the Baha’i Center of Rockford, which found them an apartment, a doctor and jobs. At first, Bounsay tired selling drawings, like he had done at the refugee camp - going to the mall or the park to find people who would pay him for their likeness. But he quickly discovered it was much harder to make a living as an artist in America than it was in Thailand. Bounsay’s sister, who was a gifted seamstress, found a job at a local upholstery shop — but she barely spoke any English. Bounsay was not yet fluent, but he knew English well enough to communicate, so he became his sister’s interpreter for her first month on the job. During that time, the shop became so busy that the owners let Bounsay try upholstery, too. He took to it like a fish to water, and thus he found a “real job” — thought he still spent as much time as he could drawing. Years passed, and Bounsay became so good at upholstery that an acquaintance hired him to train employees at Goodwill, which had received government funding for that particular training program. Ten years after Bounsay first stepped into an upholstery shop, he was opening his own store on 21st Place in Rockford; the store was on the first floor, and he, Pealuan and their baby boy lived on the second floor.

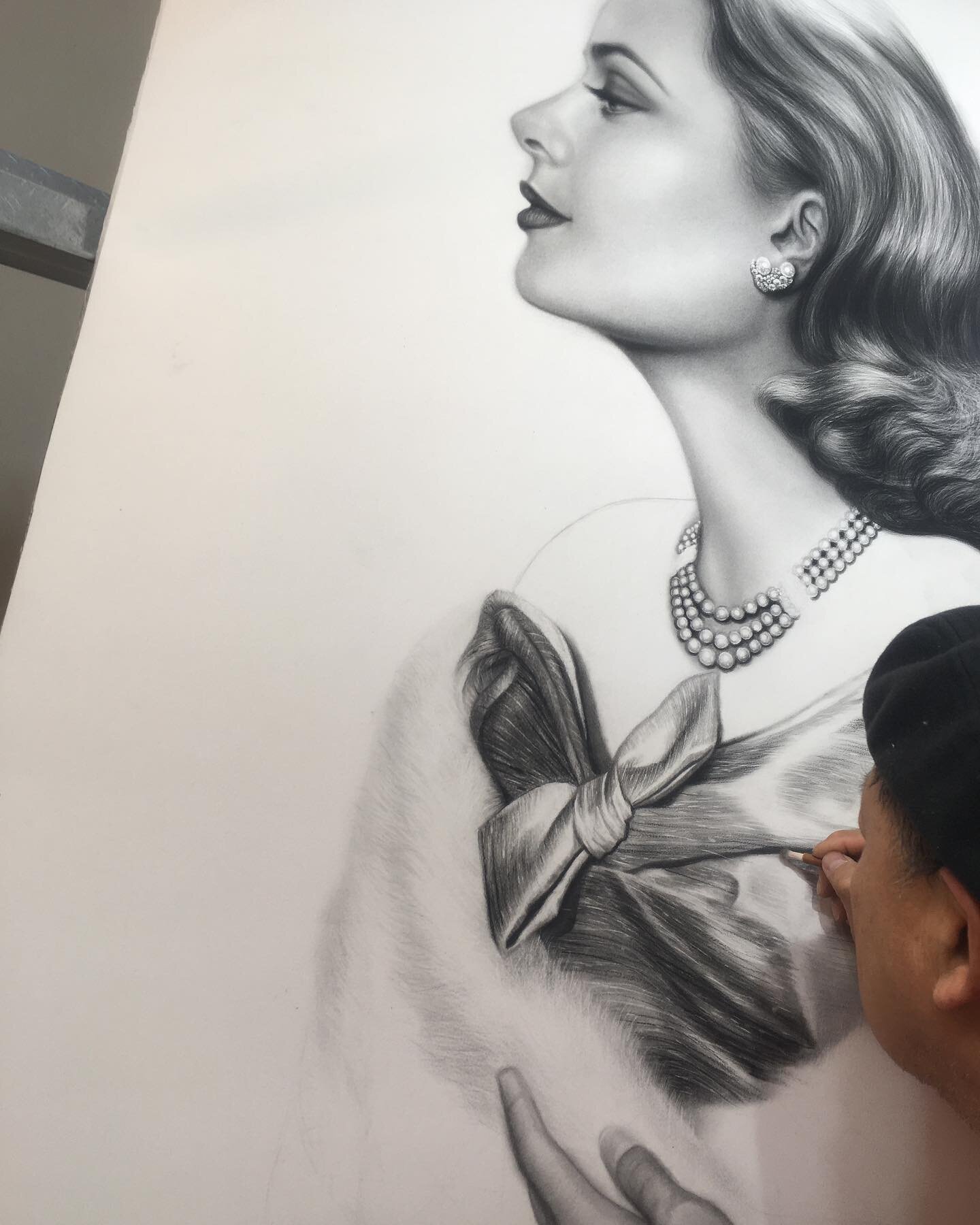

A Return to What He Loves - Bounsay and Pealuan (who came to the United States several years after her husband) had three children, and between raising his family and and managing his business, Bounsay no longer had time for drawing, When his oldest son, Andrew, was in fifth grade, his teacher asked the Pipathsouks whether they had paid for drawing classes for Andrew, because he excelled so much at art. Bounsay told her that he, himself, was an artist, so perhaps that was where Andrew had inherited his talent. Andrew was dumbfounded, because he had never seen his father pick up a piece of charcoal. He insisted that Bounsay show him what he could do, so Bounsay found a photo of Elizabeth Taylor from “Life” magazine and copied it exactly. “He said to me, ‘Dad, why did you quit drawing? You can really do this!’” says Bounsay. “I told him, yes, drawing is my passion, but when you have a family, it doesn’t work. Nevertheless, the conversation encouraged him to start drawing again when he had time, and before he knew it, he had amassed 10 drawings of female celebrities (his subject of choice), which he hung on the wall of his store. One of his customers, who was taking a class at Rockford Art Museum, showed his drawings to her instructor, and Bounsay was invited to be part of a show there. At the show, a man expressed interest in having him draw a portrait of his wife, but he wife strongly objected, saying she didn’t want a “glamorous” portrait of herself. And that, Bounsay says, is why he has never been able to make a living as an artist: His drawings of celebrities are so lifelike that it’s difficult to find people who want those kinds of portraits of themselves. “I knew I should keep my drawings as a hobby only,” he says. “It’s too difficult to find enough people who want to buy what I’m creating.” But Bounsay’s children haven’t given up. Last year, his youngest daughter, Sophia, arranged for him to display his drawings in a show at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He met a museum curator there, who told him he would need at least 100 drawings to launch his own show. Bounsay decided to go for it. Creating 100 works might have been tough a few years ago, but Andrew has paid for their mortgage and most of their expenses so his father and mother don’t have to worry much about finances, even while they are still running their business. “It seemed like a very natural thing to do, given everything they’ve done for us,” says Andrew, who is now 30 and a robotics engineer in San Francisco. So Bounsay has his work cut out for him — he’s determined to see it through. “This is one last chance for me to fulfill my childhood dream,” he says. “I am not a young man anymore, and if I don’t help myself, who will? Even if there’s a 1 percent chance that I will succeed, I want to go for it. I tell my children, in life you have to try your very best, no matter what.”